Basic cheatsheets

Source

At least 80% of this cheatsheet was inspired by Google Project Management on Coursera. I am not pretending to authority of these materials.

Comparing Waterfall and Agile Approaches

Key Distinction

Waterfall and Agile are implemented in many different ways on many different projects, and some projects may use aspects of each. The chart below briefly describes and compares Waterfall and Agile approaches. You can use it as a quick reference tool, but be aware that in practice, the differences between these two approaches may not always be clearly defined.

Waterfall vs Agile Comparison Table

| Aspect | Waterfall | Agile |

|---|---|---|

| Project Manager’s Role | Project manager serves as an active leader by prioritizing and assigning tasks to team members | Scrum Master acts primarily as a facilitator, removing any barriers the team faces. Team shares more responsibility in managing their own work |

| Scope | Project deliverables and plans are well-established and documented in early stages. Changes go through formal change request process | Planning happens in shorter iterations and focuses on delivering value quickly. Subsequent iterations are adjusted based on feedback |

| Schedule | Follows a mostly linear path through initiating, planning, executing, and closing phases | Time is organized into Sprints. Each Sprint has defined duration with planned deliverables |

| Cost | Costs are controlled by careful upfront estimation and close monitoring throughout | Costs and schedule could change with each iteration |

| Quality | Project manager defines quality criteria and plans at project start | Team solicits ongoing stakeholder input and implements regular improvements |

| Communication | Project manager regularly communicates progress on milestones to stakeholders | Team maintains consistent communication between users and project team |

| Stakeholders | Project manager actively manages stakeholder engagement | Team frequently delivers to stakeholders and adjusts based on feedback |

Lean and Six Sigma Methodologies

Lean Methodology

Definition

Lean methodology is often referred to as Lean Manufacturing because it originated in the manufacturing world. The main principle is removing waste within operations by optimizing processes and adding value at each production phase.

Eight Types of Waste in Lean

Today’s Lean Manufacturing recognizes eight types of operational waste:

- Defects

- Excess processing

- Overproduction

- Waiting

- Inventory

- Transportation

- Motion

- Non-utilized talent

Common Causes of Waste

Key Issues

In manufacturing, these wastes often stem from:

- Lack of proper documentation

- Missing process standards

- Poor understanding of customer needs

- Ineffective communication

- Insufficient process control

- Inefficient process design

- Management failures

Creating OKRs for your project

What are OKRs?

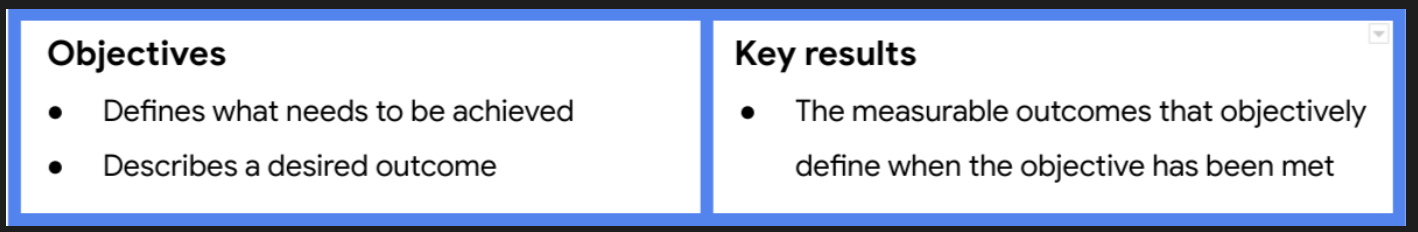

OKR stands for objectives and key results. They combine a goal and a metric to determine a measurable outcome.

Objectives: Defines what needs to be achieved; describes a desired outcome. Key results: The measurable outcomes that objectively define when the objective has been met

Objectives: Defines what needs to be achieved; describes a desired outcome. Key results: The measurable outcomes that objectively define when the objective has been met

Company-wide OKRs are used to set an ultimate goal for an entire organization, whole team, or department. Project-level OKRs describe the focused results each group will need to achieve in order to support the organization.

OKRs and project management

As a project manager, OKRs can help you expand upon project goals and further clarify the deliverables you’ll need from the project to accomplish those goals. Project-level OKRs help establish the appropriate scope for your team so that you can say “no” to requests that may get in the way of them meeting their objectives. You can also create and use project-level OKRs to help motivate your team since OKRs are intended to challenge you to push past what’s easily achievable.

Creating OKRs for your project

Set your objectives

Project objectives should be aspirational, aligned with organizational goals, action-oriented, concrete, and significant. Consider the vision you and your stakeholders have for your project and determine what you want the project team to accomplish in 3–6 months.

Examples:

-

Build the most secure data security software

-

Continuously improve web analytics and conversions

-

Provide a top-performing service

-

Make a universally-available app

-

Increase market reach

-

Achieve top sales among competitors in the region

Strong objectives meet the following criteria. They are:

-

Aspirational

-

Aligned with organizational goals

-

Action-oriented

-

Concrete

-

Significant

To help shape each objective, ask yourself and your team:

-

Does the objective help in achieving the project’s overall goals?

-

Does the objective align with company and departmental OKRs?

-

Is the objective inspiring and motivational?

-

Will achieving the objective make a significant impact?

Develop key results

Next, add 2–3 key results for each objective. Key results should be time-bound. They can be used to indicate the amount of progress to achieve within a shorter period or to define whether you’ve met your objective at the end of the project. They should also challenge you and your team to stretch yourselves to achieve more.

Examples:

-

X% new signups within first quarter post launch

-

Increase advertiser spend by X% within the first two quarters of the year

-

New feature adoption is at least X% by the end of the year

-

Maximum 2 critical bugs are reported monthly by customers per Sprint

-

Maintain newsletter unsubscribe rate at X% this calendar year

Strong key results meet the following criteria:

-

Results-oriented—not a task

-

Measurable and verifiable

-

Specific and time-bound

-

Aggressive yet realistic

To help shape your key results, ask yourself and your team the following:

-

What does success mean?

-

What metrics would prove that we’ve successfully achieved the objective?

OKR development best practices

Here are some best practices to keep in mind when writing OKRs:

-

Think of your objectives as being motivational and inspiring and your key results as being tactical and specific. The objective describes what you want to do and the key results describe how you’ll know you did it.

-

As a general rule, try to develop around 2–-3 key results for each objective.

-

Be sure to document your OKRs and link to them in your project plan.

OKRs versus SMART goals

Earlier in this lesson, you learned how to craft SMART goals for your project. While SMART goals and OKRs have some similarities, there are key differences, as well. The following article describes how SMART goals and OKRs are similar, how they differ, and when you might want to use one or the other: Understanding the Unique Utility of OKRs vs. SMART Goals

To learn more how OKRs work to help project managers define and create measurable project goals and deliverables, check out the following resources:

-

OKR TED Talk video (John Doerr, the founder of OKRs, explains why the secret to success is setting the right goals.)

Key Differences Between KPI and OKR

| KPI (Key Performance Indicator) | OKR (Objectives and Key Results) | |

|---|---|---|

| What it is | A metric to measure performance | A goal-setting framework for achieving strategic aims |

| Purpose | Track efficiency and stability of operations | Drive focus, alignment, and growth |

| Structure | A number or percentage target | One Objective with 2–5 measurable Key Results |

| Ambition level | Targets are meant to be consistently achieved | Designed to be ambitious (70–80% completion is OK) |

| Review frequency | Ongoing, tracked weekly/monthly | Set quarterly or annually |

| Use case | Operational performance monitoring (e.g. sales, support) | Strategic alignment across teams and initiatives |

How to Combine OKRs and KPIs Effectively

Step 1: Translate the CEO’s Directive into Company-Wide OKRs

Example CEO goal:

“Become the market leader and improve customer satisfaction.”

Company OKR Example:

Objective: Become the top-rated service in our industry

-

KR1: Increase market share from 15% to 20%

-

KR2: Raise CSAT to 92%

-

KR3: Launch 2 new service features by Q4

Step 2: Cascade OKRs from Company → Departments → Teams → Individuals

| Level | Type | Example Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Company | Strategic OKRs | ”Become market leader in service” |

| Department | Tactical OKRs | ”Enhance support efficiency” |

| Team | Team OKRs | ”Automate ticket handling workflows” |

| Individual | Personal OKRs & KPIs | ”Resolve 40+ tickets/day with CSAT ≥ 4.8” |

Step 3: Link KPIs to OKRs for Performance Tracking

OKRs provide strategic direction, while KPIs measure performance execution.

| OKR Key Result | Supporting KPI |

|---|---|

| Raise CSAT to 92% | Weekly customer satisfaction score |

| Reduce response time to 1 hour | Average ticket response time |

| Grow repeat purchases by 20% | Customer retention rate, LTV |

Step 4: Use Tools and Dashboards for Visibility

-

Use OKR tools (e.g., Weekdone, Perdoo, Gtmhub) for alignment.

-

Track KPIs via BI dashboards, CRM tools, or Excel.

Step 5: Communicate Clearly and Engage Teams

-

Host a company-wide OKR kickoff to explain top-level goals.

-

Have managers guide teams in writing team- and individual-level OKRs.

-

Align individual KPIs with OKR key results for consistency and accountability.

** In Summary:**

- OKRs = Focus, direction, ambition

- KPIs = Measurement, control, performance

- Together they ensure: strategic alignment + operational execution

Gathering information to define scope

Imagine that while working in a restaurant management group, your manager calls and asks you to “update the dining space,” then quickly hangs up the phone without providing further instruction. In this initial handoff from the manager, you are missing a lot of information. How do you even know what to ask?

Let’s quickly recap the concept of scope. The scope provides the boundaries for your project. You define the scope to help identify necessary resources, resource costs, and a schedule for the project.

In the situation we just described, here are some questions you might ask your manager in order to get the information you need to define the scope of the project:

Stakeholders

-

How did you arrive at the decision to update the dining space?

-

Did the request originate from the restaurant owner, customers, or other stakeholders?

-

Who will approve the scope for the project?

Goals

-

What is the reason for updating the dining space?

-

What isn’t working in the current dining space?

-

What is the end goal of this project?

Deliverables

-

Which dining space is being updated?

-

What exactly needs to be updated?

-

Does the dining space need a remodel?

Resources

-

What materials, equipment, and people will be needed?

-

Will we need to hire contractors?

-

Will we need to attain a floor plan and building permits?

Budget

- What is the budget for this project? Is it fixed or flexible?

Schedule

-

How much time do we have to complete the project?

-

When does the project need to be completed?

Flexibility

-

How much flexibility is there?

-

What is the highest priority: hitting the deadline, sticking to the budget, or making sure the result meets all the quality targets?

Strategies for controlling scope creep

The scope of a project can get out of control quickly—so quickly that you may not even notice it.

Warning

Scope creep is when a project’s work starts to grow beyond what was originally agreed upon during the initiation phase. Scope creep can put stress on you, your team, and your organization, and it can put your project at risk. The effects of scope creep can hinder every aspect of the project, from the schedule to the budget to the resources, and ultimately, its overall success.

Here are some best practices for scope management and controlling scope creep:

-

Define your project’s requirements. Communicate with your stakeholders or customers to find out exactly what they want from the project and document those requirements during the initiation phase.

-

Set a clear project schedule. Time and task management are essential for sticking to your project’s scope. Your schedule should outline all of your project’s requirements and the tasks that are necessary to achieve them.

-

Determine what is out of scope. Make sure your stakeholders, customers, and project team understand when proposed changes are out of scope. Come to a clear agreement about the potential impacts to the project and document your agreement.

-

Provide alternatives. Suggest alternative solutions to your customer or stakeholder. You can also help them consider how their proposed changes might create additional risks. Perform a cost-benefit analysis, if necessary.

-

Set up a change control process. During the course of your project, some changes are inevitable. Determine the process for how each change will be defined, reviewed, and approved (or rejected) before you add it to your project plan. Make sure your project team is aware of this process.

-

Learn how to say no. Sometimes you will have to say no to proposed changes. Saying no to a key stakeholder or customer can be uncomfortable, but it can be necessary to protect your project’s scope and its overall quality. If you are asked to take on additional tasks, explain how they will interfere with the budget, timeline, and/or resources defined in your initial project requirements.

-

Collect costs for out-of-scope work. If out-of-scope work is required, be sure to document all costs incurred. That includes costs for work indirectly impacted by the increased scope. Be sure to indicate what the charges are for.

Triple Constraint

project managers may refer to the triple constraint model to manage scope and control scope creep. It can serve as a valuable tool to help you negotiate priorities and consider trade-offs.

project managers may refer to the triple constraint model to manage scope and control scope creep. It can serve as a valuable tool to help you negotiate priorities and consider trade-offs.

For further reading on utilizing the triple constraint model in real-life scenarios as a project manager and how the triple constraint model has evolved over time, we recommend checking out this article: A Project Management Triple Constraint Example & Guide.

Essential project roles

The project manager

Although all team members are responsible for their individual parts of the project, the project manager is responsible for the overall success of the team, and ultimately, the project as a whole. A project manager understands that paying close attention to team dynamics is essential to successfully completing a project, and they use team-building techniques, motivation, influencing, decision-making, and coaching skills, to keep their teams strong.

Project managers integrate all project work by developing the project management plan, directing the work, documenting reports, controlling change, and monitoring quality.

In addition, project managers are responsible for balancing the scope, schedule, and cost of a project by managing engagement with stakeholders. When managing engagement with stakeholders, project managers rely on strong communication skills, political and cultural awareness, negotiation, trust-building, and conflict management skills.

Stakeholders

Have you ever heard the phrase “the stakes are high”? When we talk about “stakes,” we are referring to the important parts of a business, situation, or project that might be at risk if something goes wrong. To hold stake in a business, situation, or project means you are invested in its success. There will often be several parties that will hold stake in the outcome of a project. Each group’s level of investment will differ based on how the outcome of the project may impact them**.** Stakeholders are often divided into two groups: primary stakeholders, also known as key stakeholders, and secondary stakeholders. A primary stakeholder is directly affected by the outcome of the project, while a secondary stakeholder is indirectly affected by the outcome of the project.

Primary stakeholders usually include team members, senior leaders, and customers. For example, imagine that you are a project manager for a construction company that is commissioned to build out a new event space for a local catering company. On this project, the owners of the catering company would be primary stakeholders since they are paying for the project.

An example of a secondary stakeholder might be the project’s point of contact in legal. While the project outcome might not affect them directly, the project itself would impact their work when they process the contract. Each project will have a different set of stakeholders, which is why it’s important for the project manager to know who they are, what they need, and how to communicate with them.

Project team members

Every successful team needs strong leadership and membership, and project management is no exception! Project team members are also considered primary stakeholders, since they play a crucial role in getting the job done. Your team members will vary depending on the type, complexity, and size of the project. It’s important to consider these variables as you select your project team and begin to work with them. Remember that choosing teammates with the right technical skills and interpersonal skills will be valuable as you work to meet your project goals. If you are not able to select your project team, be sure to champion diversity and build trust to create harmony within the team.

Sponsor

The project sponsor is another primary stakeholder. A sponsor initiates the project and is responsible for presenting a business case for its existence, signing the project charter, and releasing resources to the project manager. The sponsor is very important to the project, so it’s critical to communicate with them frequently throughout all project phases. In our construction company example, the CEO could also be the project sponsor.

Prioritizing stakeholders and generating their buy-in

In this lesson, you are learning to complete a stakeholder analysis and explain its significance. Let’s focus here on how to prioritize the various types of stakeholders that can exist on a project, generate stakeholder buy-in, and manage their expectations.

Conducting a stakeholder analysis

Let’s review the key steps in the stakeholder analysis:

-

Make a list of all the stakeholders the project impacts. When generating this list, ask yourself: Who is invested in the project? Who is impacted by this project? Who contributes to this project?

-

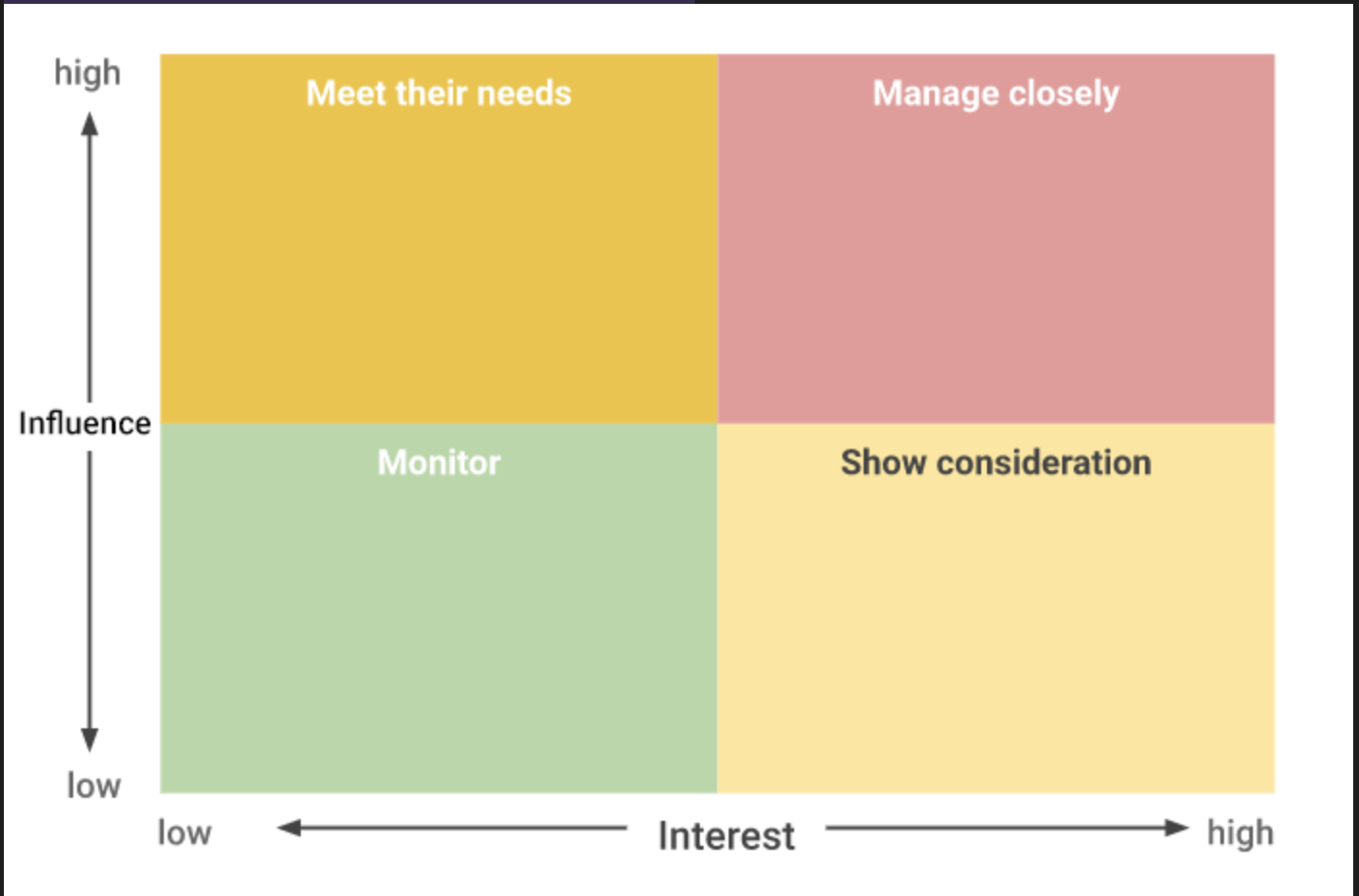

Determine the level of interest and influence for each stakeholder—this step helps you determine who your key stakeholders are. The higher the level of interest and influence, the more important it will be to prioritize their needs throughout the project.

-

Assess stakeholders’ ability to participate and then find ways to involve them. Various types of projects will yield various types of stakeholders—some will be active stakeholders with more opinions and touchpoints and others will be passive stakeholders, preferring only high-level updates and not involved in the day-to-day. That said, just because a stakeholder does not participate as often as others does not mean they are not important. There are lots of factors that will play a role in determining a stakeholder’s ability to participate in a project, like physical distance from the project and their existing workload.

Visualizing your analysis

Quadrant 1: High Influence, High Interest (Upper Right)

Quadrant 1: High Influence, High Interest (Upper Right)

Stakeholders in this quadrant have a significant influence on the project and are highly interested in its outcome. They can greatly impact project decisions and success. Examples might include project sponsors, key executives, or regulatory authorities. Responses for this quadrant include:

-

Engagement and Involvement:

-

Keep these stakeholders well-informed and engaged throughout the project lifecycle.

-

Involve them in decision-making processes, seeking their input and feedback.

-

Address their concerns promptly and effectively.

-

-

Regular Communication:

-

Schedule regular meetings or updates to keep them informed about project progress and any issues.

-

Tailor communication to their preferences and needs to ensure they remain supportive and engaged.

-

Quadrant 2: High Influence, Low Interest (Upper Left)

Stakeholders in this quadrant have high influence but may not be deeply interested in the day-to-day project details. They might include senior managers who need to be informed but may not be actively engaged. Responses for this quadrant include:

-

Executive Summaries:

-

Provide high-level summaries of project progress and key decisions for their review.

-

Focus on the impact of the project on organizational goals and objectives.

-

-

Periodic Updates:

- Provide periodic briefings or updates to ensure they are informed of major milestones and critical project changes.

Quadrant 3: Low Influence, High Interest (Bottom Right)

Stakeholders in this quadrant have a high interest in the project but relatively low influence on its outcome. They are typically looking for updates and information about the project. Responses for this quadrant include:

-

Regular Updates:

-

Communicate project progress, risks, and updates to keep them engaged and informed.

-

Address their queries and concerns promptly to maintain their interest.

-

-

Stakeholder Feedback:

- Seek their feedback on project plans, progress, and outcomes to ensure their perspective is considered.

Quadrant 4: Low Influence, Low Interest (Bottom Left)

Stakeholders in this quadrant have low influence on the project and limited interest in its details. They might include lower-level employees or departments not directly impacted by the project. Responses for this quadrant include:

-

General Communication:

-

Share general updates about the project’s overall progress without overwhelming them with details.

-

Address any specific questions they may have, but avoid unnecessary inundation with project-related information.

-

-

Minimal Engagement:

- Maintain a basic level of communication and engagement to keep them aware of the project without distracting them from their regular responsibilities.

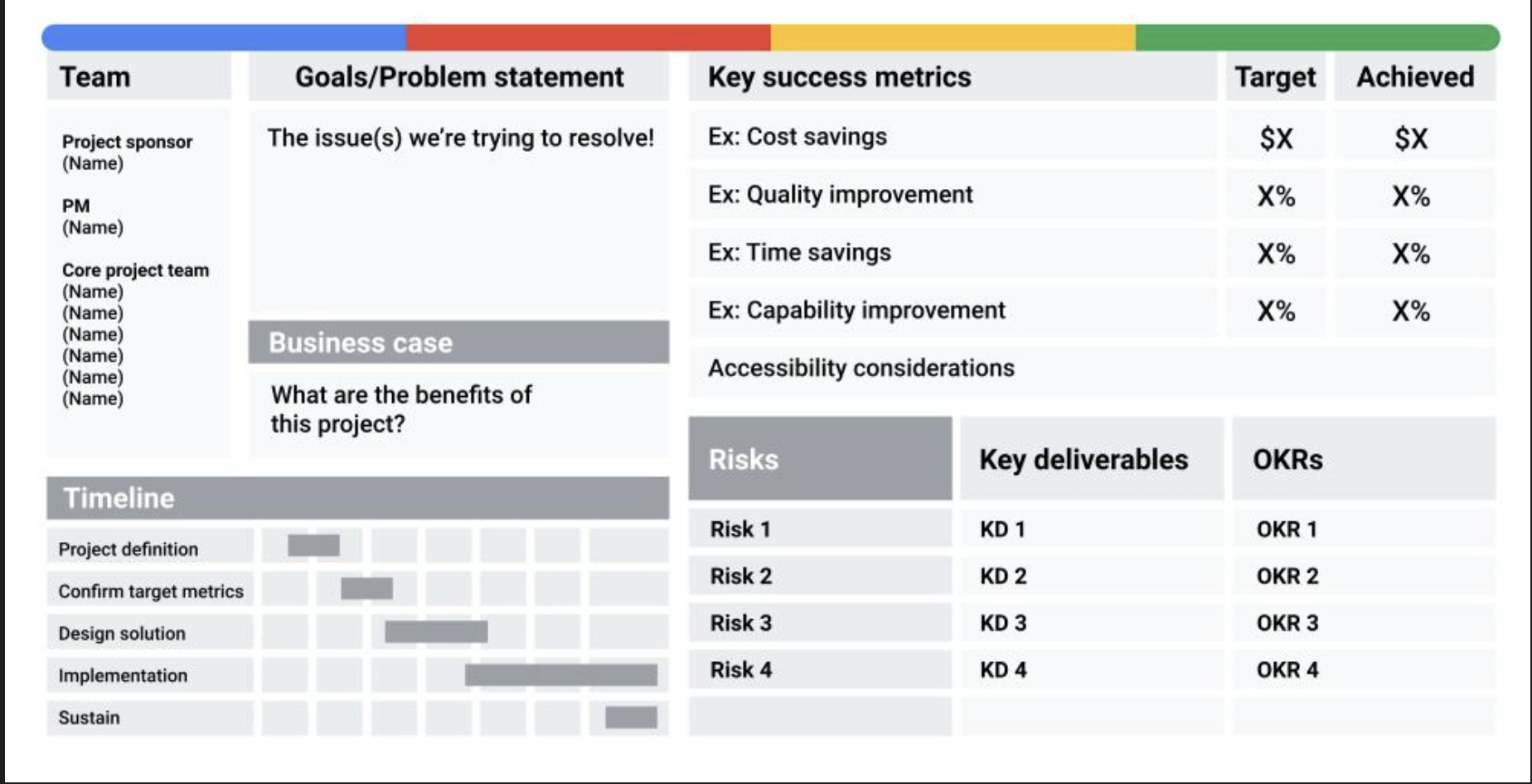

Project charters: Elements and formats

A project charter clearly defines the project and outlines the necessary details for the project to reach its goals. A well-documented project charter can be a project manager’s secret weapon to success. In this reading, we will go over the function, key elements, and significance of a project charter and learn how to create one.

Project charters will vary but usually include some combination of the following key information:

- introduction/project summary

- goals/objectives

- business case/benefits and costs

- project team

- scope

- success criteria

- major requirements or key deliverables

- budget

- schedule/timeline or milestones

- constraints and assumptions

- risks

- OKRs

- approvals

Example of a project charter

Example of a project charter

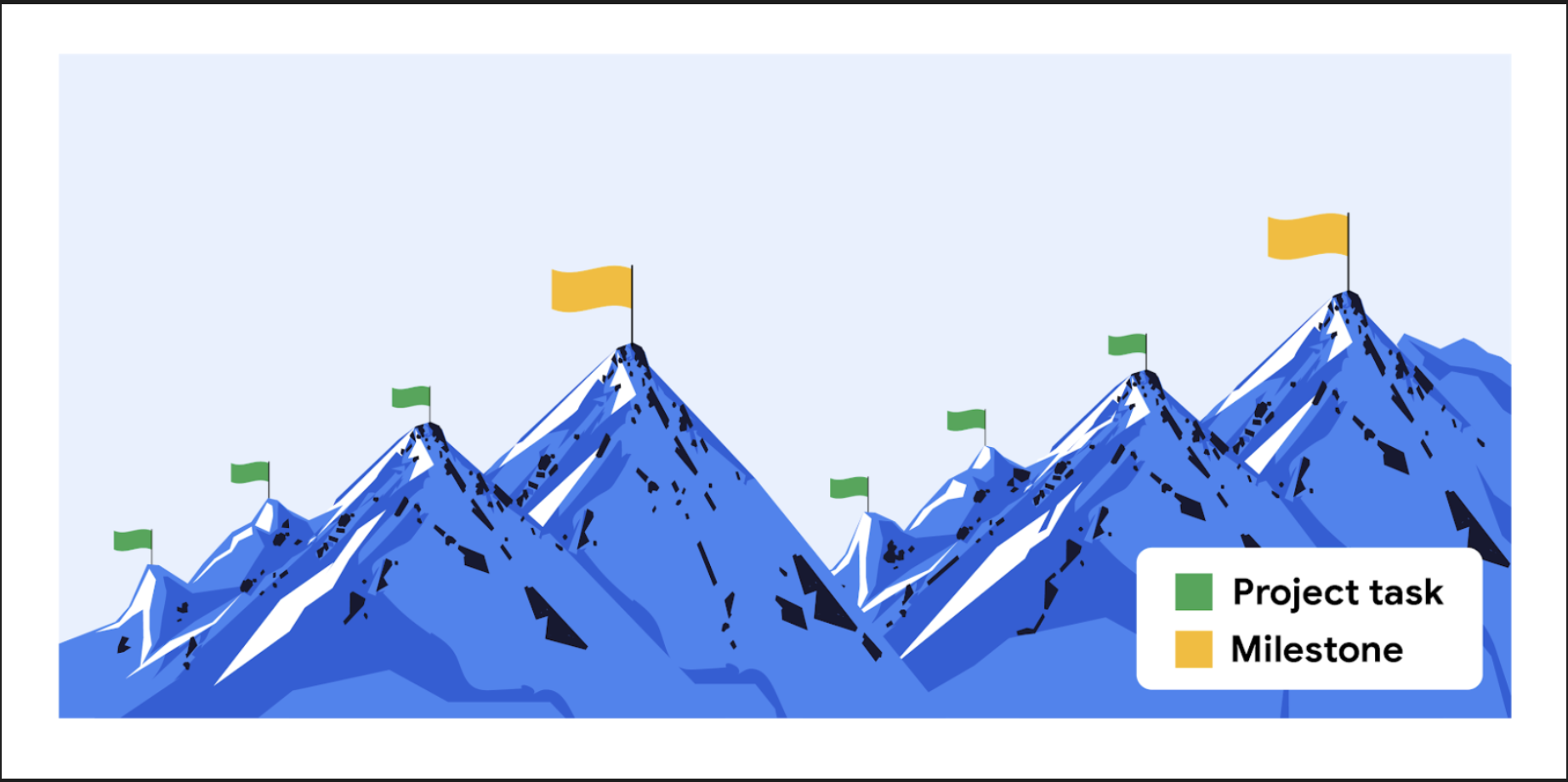

Setting milestones: Best practices

Set tasks to identify milestones

Setting tasks can help you clearly define milestones. You can do this in two ways:

-

Top-down scheduling: In this approach, the project manager lays out the higher-level milestones, then works to break down the effort into project tasks. The project manager works with their team to ensure that all tasks are captured.

-

Bottom-up scheduling: In this approach, the project manager looks at all of the individual tasks that need to be completed and then rolls those tasks into manageable chunks that lead to a milestone.

Milestone-setting pitfalls

Here are some things to avoid when setting milestones:

-

Don’t set too many milestones. When there are too many milestones, their importance is downplayed. And, if milestones are too small or too specific, you may end up with too many, making the project look much bigger than it really is to your team and stakeholders.

-

Don’t mistake tasks for milestones. Remember that milestones should represent moments in time, and in order to map out how you will get to those moments, you need to assign smaller tasks to each milestone.

-

Don’t list your milestones and tasks separately. Make sure that tasks and milestones can be visualized together in one place, such as a project plan. This will help ensure that you are hitting your deadlines and milestones.

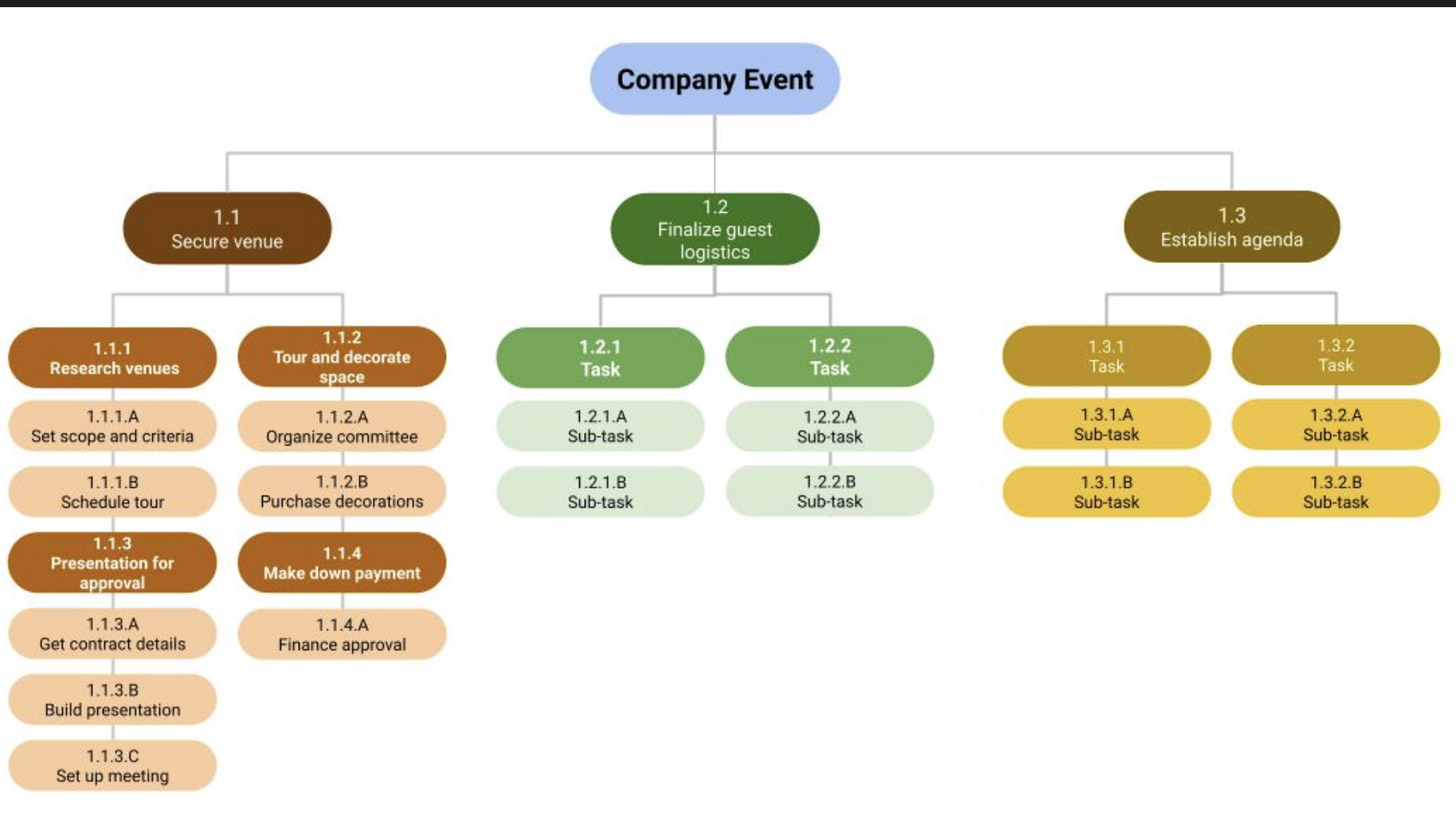

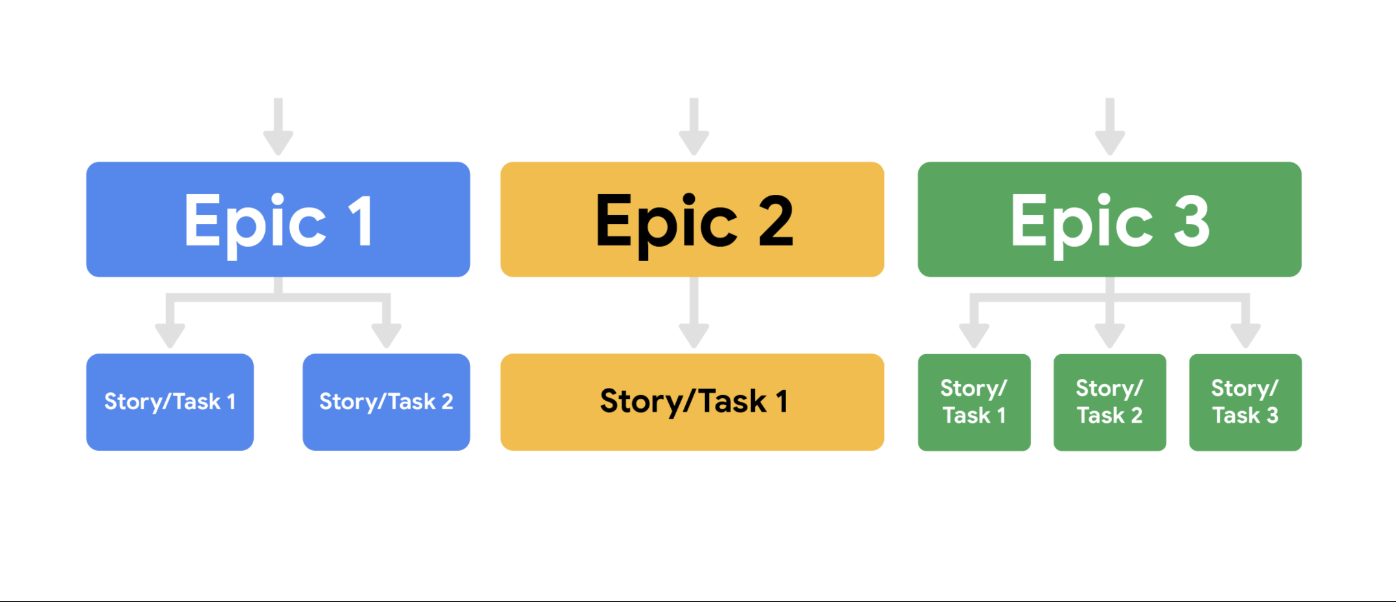

Breaking down the work breakdown structure

WBS is a deliverable-oriented breakdown of a project into smaller components. It’s a tool that sorts the milestones and tasks of a project into a hierarchy, in the order they need to be completed.

A thorough WBS gives you a visual representation of a project and the tasks required to deliver each milestone. It makes it easier to understand all of the essential project tasks, such as estimating costs, developing a schedule, assigning roles and responsibilities, and tracking progress. Think of each piece of information as part of the overall project puzzle—you can’t successfully navigate through the tasks without understanding how they all fit together. For instance, many smaller tasks may ladder up to a larger task or milestone.

Steps to build a WBS

As a reminder, here are three main steps to follow when creating a WBS:

-

Start with the high-level, overarching project picture. Brainstorm with your team to list the major deliverables and milestones. Example: Imagine you are planning a company event. Your major milestones might include categories like “secure venue,” “finalize guest logistics,” and “establish agenda.”

-

Identify the tasks that need to be performed in order to meet those milestones. Example: You could break a milestone like “secure venue” down into tasks like “research venues,” “tour and decorate space,” “make down payment,” and so on.

-

Examine those tasks and break them down further into sub-tasks. Example: You could break down a task like “tour and decorate space” further into sub-tasks like “organize decorating committee,” “purchase decorations,” “assign decorating responsibilities,” and so on.

Further reading

For further learning on best practices for developing a WBS, check out this article:

Overcoming the planning fallacy

It is human nature to underestimate the amount of time and effort it takes to complete a task—from anything as simple as walking the dog to something as complex as completing a project. People generally want to remain hopeful about a positive outcome, and this is a great quality to have as a person. But as a project manager, this kind of optimism can also be a deficiency, especially during the planning phase of a project. Let’s examine a theory known as the planning fallacy to better understand how to set yourself up for success in the planning phase.

The planning fallacy and optimism bias

The idea of the planning fallacy was first introduced in a 1977 paper written by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, two foundational figures in the field of behavioral economics. The planning fallacy describes our tendency to underestimate the amount of time it will take to complete a task, as well as the costs and risks associated with that task, due to optimism bias. Optimism bias is when a person believes that they are less likely to experience a negative event. For example, when you are planning to walk your dog in between meetings, you might think that you can do it faster than you actually can. Optimism bias is what tells you that you are going to be able to walk your dog without being late for your next meeting. If you don’t consider things that might affect the time it will take you to walk your dog—the weather, the chance of them running into another dog and wanting to play, or the fact that they frequently get distracted while sniffing around—you might be late for your next meeting, or you might miss it altogether!

Avoiding the planning fallacy: A case study

Think about the planning fallacy in relation to yourself as a project manager. If you have planned massive efforts in your project plan with an optimism bias, this planning fallacy could have a major impact on your project execution. You could set your team up for failure by not giving them enough time to complete their tasks, causing work to have to be redone or missing opportunities to execute the project more efficiently.

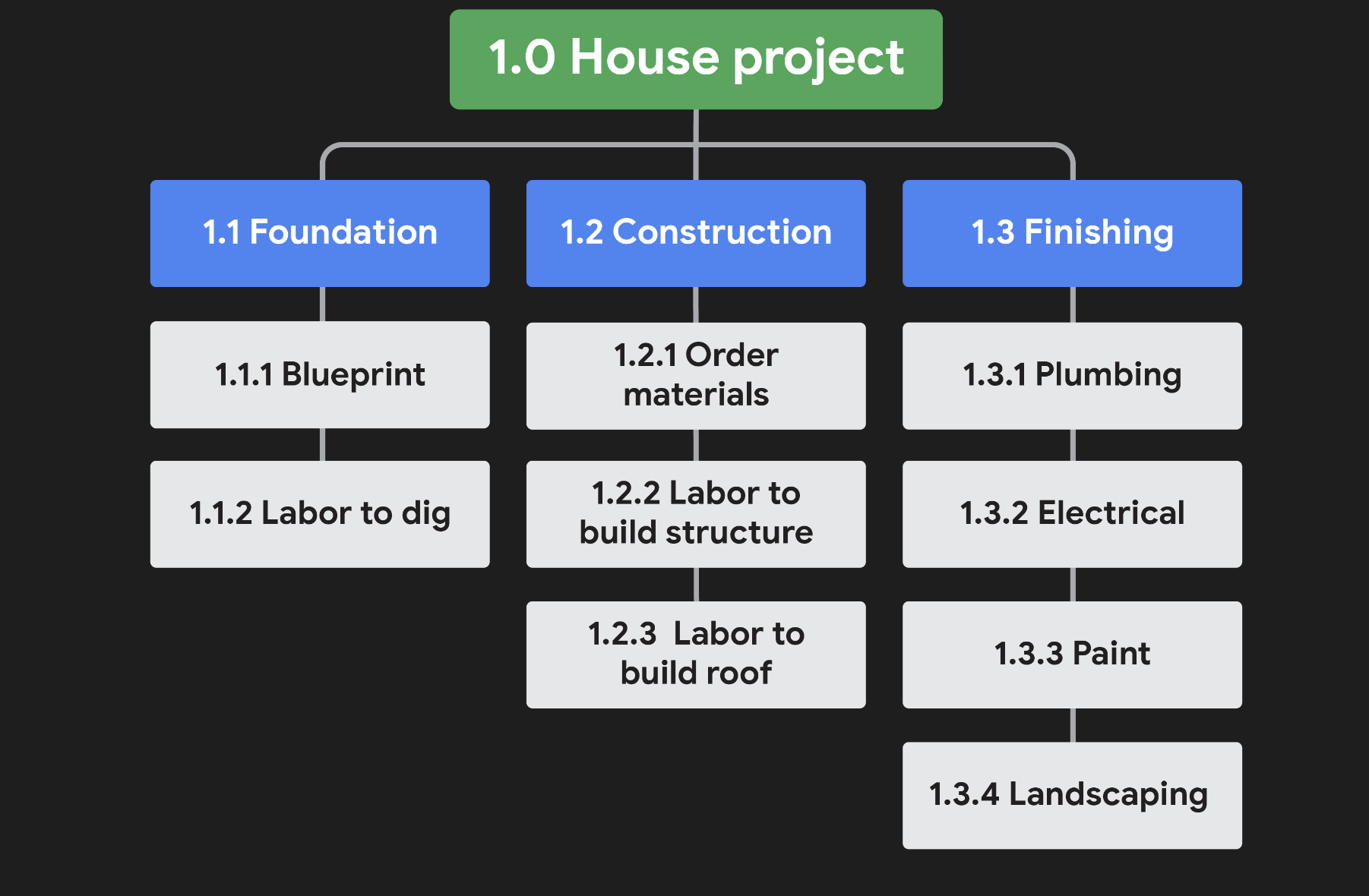

Let’s examine how this happens. David is a project manager responsible for a home construction project. Let’s check out his Work Breakdown Structure (WBS):

Working through his plan, David knows that certain things need to happen for the house to be completed. He has to order materials, the materials have to be delivered, the contractor has to actually build the house, and there needs to be time for completing finishing touches and adjustments. The time estimations for those major tasks might break down like this:

| Task | Estimated Duration |

|---|---|

| Foundation | 2 weeks |

| Construction | 4 weeks |

| Adjustments | 4 weeks |

After creating a WBS and a time estimation chart, David estimates that the construction project will take a total of ten weeks. This sounds perfect because it meets his delivery requirement. If David is unaware of the planning fallacy, he may think his plan is solid and that his team is on their way to building the house within the target timeline!

Fortunately, David is mindful of the planning fallacy. He examines the time estimates more carefully. He considers risks like weather delays or crew members calling out sick, which could set the project’s completion date back. He meets with his team members and other stakeholders to help him uncover other possible risks that could affect the project timeline. After carefully gathering information, he adjusts the time estimates, adding task buffers to some of the project tasks to account for the potential risks.

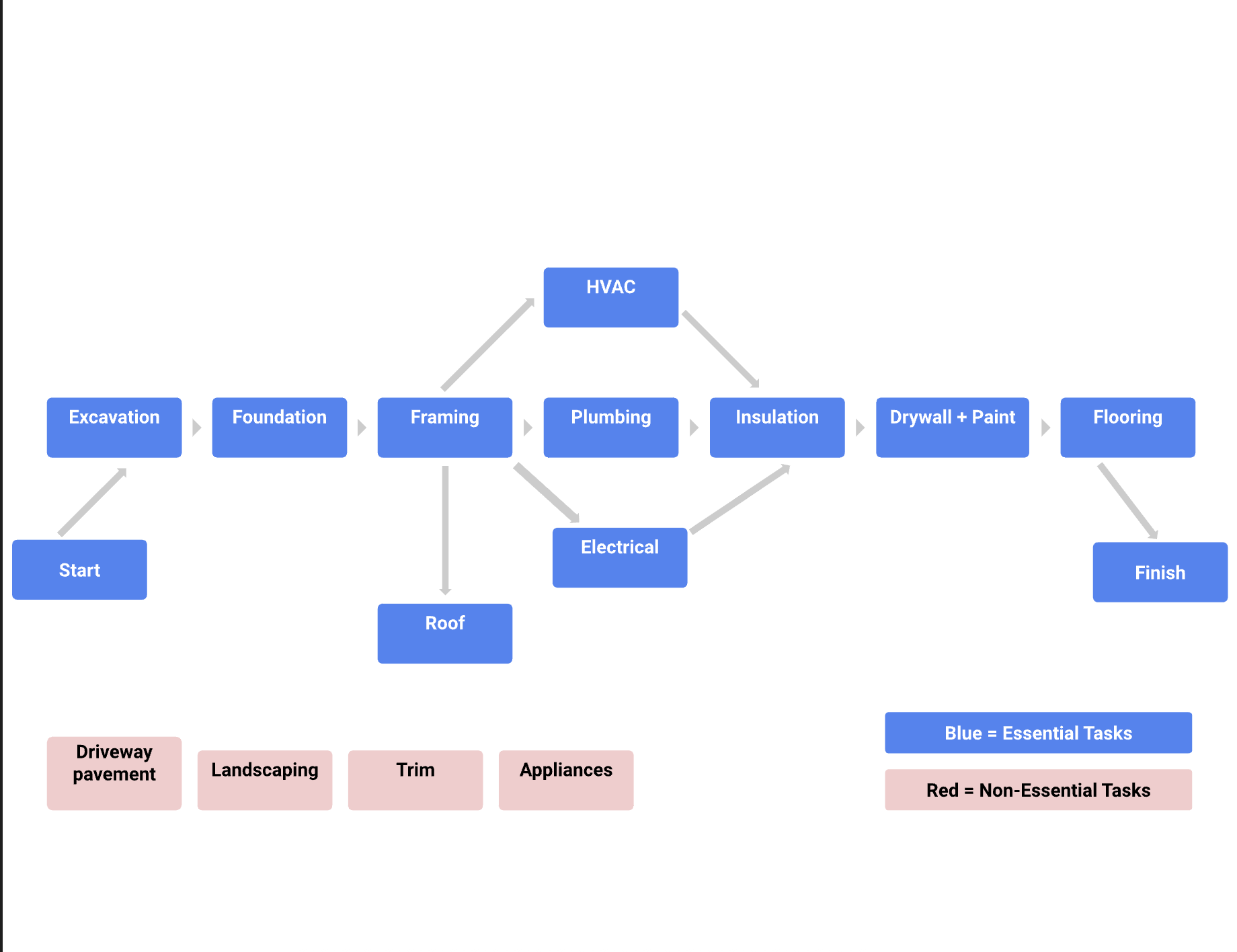

Creating a critical path

The critical path helps you determine the essential tasks that need to be completed on your project to meet your end goal and how long each task will take. The critical path also provides a quick reference for critical tasks by revealing which tasks will impact your project completion date negatively if their scheduled finish dates are late or missed. A critical path can help you define the resources you need, your project baselines, and any flexibility you have in the schedule.

How to create a critical path

Step 1: Capture all tasks

The main goal in this step is to make sure that you aren’t missing a key piece of work that is required to complete your project. When creating a critical path, focus on the essential, “need to do” tasks, rather than the “nice to do” tasks that aren’t essential for the completion of the project. Here is an example of critical tasks for building the structure of a house:

| Task |

|---|

| A) Excavation |

| B) Foundation |

| C) Framing |

| D) Roof |

| E) Plumbing |

| F) Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) |

| G) Electrical |

| H) Insulation |

| I) Drywall + Paint |

| J) Flooring |

Step 2: Set dependencies

To figure out dependencies for each task, ask:

-

Which task needs to take place before this task?

-

Which task can be finished at the same time as this task?

-

Which task needs to happen right after this task?

Once you have answered these questions, you can list these dependencies next to your list of tasks:

| Task | Dependency |

|---|---|

| A) Excavation | |

| B) Foundation | A) Excavation |

| C) Framing | B) Foundation |

| D) Roof | C) Framing |

| E) Plumbing | C) Framing |

| F) HVAC | C) Framing |

| G) Electrical | C) Framing |

| H) Insulation | E) Plumbing, F) HVAC, G) Electrical |

| I) Drywall + Paint | H) Insulation |

| J) Flooring | I) Drywall + Paint |

Step 3: Create a network diagram

One common way to visualize the critical path is by creating a network diagram. Network diagrams, like the example below, sequence tasks in the order in which they need to be completed, based on their dependencies. These diagrams help visualize:

-

The path of the work from the start of the project (excavation) to the end of the project (flooring)

-

Which tasks can be performed in parallel (e.g., HVAC and plumbing) and in sequence (e.g., plumbing then insulation)

-

Which non-essential tasks are NOT on the critical path

(Long description of graphic above: Essential tasks, including Start, Excavation, Foundation, Framing, Roof, HVAC, Plumbing, Electrical, Insulation, Drywall+Paint, Flooring, and Finish, are laid out in a sequential path and highlighted in blue. Roof, HVAC, and Electrical are shown as tasks able to be done concurrently with Framing and Plumbing. Non-essential tasks are separated from essential tasks and are highlighted in red. Non-essential tasks include Driveway Pavement, Landscaping, Trim, and Appliances.)

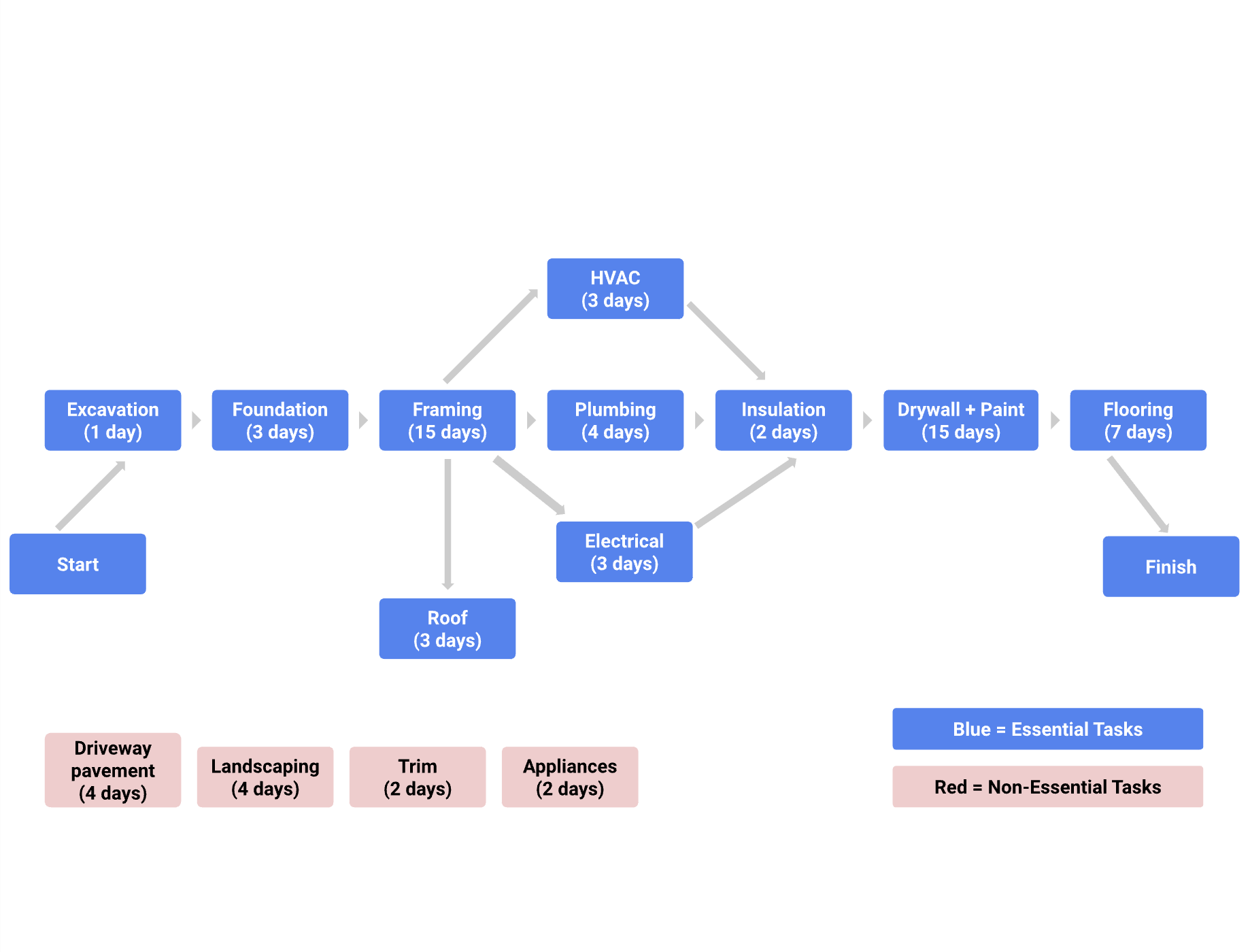

Step 4: Make time estimates

After determining tasks and dependencies, consult key stakeholders to get accurate time estimates for each task. This is a crucial step in determining your critical path. If your time estimates are significantly off, it may cause the length of your critical path to change. Time estimates can be reviewed and updated throughout the project, as necessary.

| Task | Duration | Dependency |

|---|---|---|

| A) Excavation | 1 Day | |

| B) Foundation | 3 Days | A) Excavation |

| C) Framing | 15 Days | B) Foundation |

| D) Roof | 3 Days | C) Framing |

| E) Plumbing | 4 Days | C) Framing |

| F) HVAC | 3 Days | C) Framing |

| G) Electrical | 3 Days | C) Framing |

| H) Insulation | 2 Days | E) Plumbing, F) HVAC, G) Electrical |

| I) Drywall + Paint | 15 Days | H) Insulation |

| J) Flooring | 7 Days | I) Drywall + Paint |

Step 5: Find the critical path

If you add up the durations for all of your “essential” tasks and calculate the longest possible path, you can determine your critical path. In your calculation, only include the tasks that, if they go unfinished, will impact the project’s finish date. In this example, if the “non-essential” tasks—like landscaping and driveway pavement—are not completed, the house structure completion date will not be impacted.

You can also calculate the critical path using two common approaches: the forward pass and the backward pass. These techniques are useful if you are asked to identify the earliest and latest start dates (the earliest and latest dates on which you can begin working on a task) or the slack (the amount of time that task can be delayed past its earliest start date without delaying the project).

- The forward pass refers to when you start at the beginning of your project task list and add up the duration of the tasks on the critical path to the end of your project. When using this approach, start with the first task you have identified that needs to be completed before anything else can start.

- The backward pass is the opposite—start with the final task or milestone and move backwards through your schedule to determine the shortest path to completion. When there is a hard deadline, working backwards can help you determine which tasks are actually critical. You may be able to cut some tasks—or complete them later—in order to meet your deadline.

You can read more about each of these concepts and critical path calculation methods in the following articles:

Project budgeting best practices

Here are a few tips to consider when creating your project budget:

-

Reference historical data: Your project may be similar to a previous project your organization has worked on. It is important to review how that project’s budget was handled, find out what went well, and learn from any previous mistakes.

-

Utilize your team, mentors, or manager: Get into the habit of asking for your team to double check your work to give you additional sets of eyes on your documents.

-

Time-phase your budget: Time-phased budgeting allows you to allocate costs for project tasks over the projected timeline in which those expenses are planned to take place. By looking at your tasks against a timeline, you can track and compare planned versus actual costs over time and manage changes to your budget as necessary.

-

Check, check, and double check: Make sure that your budget is accurate and error-free. Your budget will likely require approval from another department, such as finance or senior management, so do your best to ensure that it is as straightforward to understand as possible and that all of your calculations are correct.

Categorize different types of costs

There are different types of costs that your project will incur. For example, you may need to account for both direct costs and indirect costs in your project budget. Categorize these different types of costs in your budget so that you can ensure you are meeting the requirements of your organization and customer.

Direct costs

These are costs for items that are necessary in order to complete your project. These costs can include:

-

Wages and salaries of employees and contractors

-

Materials costs

-

Equipment rental costs

-

Software licenses

-

Project-related travel and transportation costs

-

Staff training

Indirect costs

These are costs for items which do not directly lead to the completion of your project but are still essential for the project team to do their work. They are also referred to as overhead costs. These costs can include:

-

Administrative costs

-

Utilities

-

Insurance

-

General office equipment

-

Security

Develop a baseline budget

A baseline budget is an estimate of project costs that you start with at the beginning of your project. Once you have created a budget for your project and gotten it approved, you should publish this baseline and use it to compare against actual performance progress. This will give you insight into how your project budget is doing and allow you to make informed adjustments.

It is important to continually monitor your project budget and make changes if necessary. Be aware that budget updates can require the same approvals as your initial budget. Also, you should “re-baseline” your budget if you make significant changes. Re-baselining refers to when you update or modify a project’s baseline as a result of any approved change to the schedule, cost, or deliverable content. For example, if you have a significant change in your project scope, your budget will likely be impacted. In this instance, you would need to re-baseline in order to adhere to a realistic budget.

Perform a reserve analysis

A reserve analysis will help you account for any buffer funds you may need. First, review all potential risks to your project and determine if you need to add buffer funds, also referred to as a contingency budget. These funds are necessary because new costs that you did not expect are likely to happen throughout the project. You may also want to account for cost of quality in your overall project budget. The cost of quality refers to all of the costs that are incurred to deliver a quality product or service, which can extend beyond material resources. This includes addressing issues with products, processes, or tasks, along with internal and external failure costs. One example would be having to redesign a product or service due to defects. A defect could mean refunds to customers, time and money required to create a new product or service, and multiple other potential costs affecting the client.

Helpful budget templates

Budget templates are a useful tool for helping you estimate, track, and maintain a project budget. Below, you will find a few different budget templates that you can use for future projects. Each of these templates is formatted in a digital spreadsheet.

Microsoft Excel Budget Templates

Microsoft Excel Website Budget Template (applicable to any project)

Google Sheets Budget Template (Note: You will need to be signed in to a Google account in order to make a copy of the template.)

Overcoming budgeting challenges

Challenge 1: Budget pre-allocation

You may encounter situations where your budget is already set before you even start the project. This is known as budget pre-allocation. Some organizations follow strict budgeting cycles, which can lead to cost estimations taking place before the scope of the project is completely defined.

If you are given a pre-allocated budget, it is important to work with your customer to set expectations on scope and deliverables within the allocated budget. To deliver a great product within your allocated budget will require detailed planning.

A pre-allocated budget should also be routinely monitored to ensure the amounts you have budgeted are sufficient to meet your costs. Be sure to carefully track all expenses in your budget. Regularly match these expenses against your pre-allocated budget to ensure you have sufficient funds for the remainder of your project.

Part of that planning includes making sure that you are tracking fixed and time- and materials-based expenses. Fixed contracts are usually paid for when certain milestones are reached. Time and materials contracts are usually paid for monthly, based on the hours worked and other fees associated with the work, such as travel and meal expenses.

Challenge 2: Inaccurately calculating TCO

Another budgeting pitfall you should try to avoid is underestimating the total cost of ownership (TCO) for project resources. TCO takes into account multiple elements that contribute to the cost of an item. It factors in the expenses associated with a product or service over its lifetime, rather than just upfront costs.

Let’s relate TCO to something more common, like owning a vehicle. Let’s say you buy a vehicle for a certain price, but then you also pay for things related to the vehicle, such as license fees, registration fees, and maintenance. If you add all of this up, you have your TCO for that vehicle. So now that you know what your TCO is, you may consider those fees before you buy your next vehicle. For example, you might opt for a vehicle with fewer maintenance requirements than one that requires more frequent service, since you know that will save you money overall.

The same concept applies to budgeting on a project. If you have a service requirement for a software technology that your team is using, for example, then it is important to budget for the costs of maintenance for that service. Additional types of costs you may need to account for when calculating TCO include warranties, supplies, required add-on costs, and upgrade costs.

Challenge 3: Scope creep

Scope creep is when changes, growth, and other factors affect the project’s scope at any point after the project begins. Scope creep causes additional work that wasn’t planned for, so scope creep can also impact your budget.

There are several factors that can lead to scope creep, such as:

-

A vague Statement of Work (SoW)

-

Conversations and agreements about the project that aren’t officially documented

-

Unattainable timeframes and deadlines

-

Last-minute asks from priority stakeholders

Addressing these factors as you plan your project can help prevent scope creep from impacting your budget.

Introduction to budgeting terms

Cash flow

Cash flow is the inflow and outflow of cash on your project. As a project manager, this is important to understand because you need funding (cash into your project) to keep your project running.

Cash that comes into your project allows you to maintain and compensate resources and pay invoices for materials or outside services. In some cases, a project may start out with all of the cash it will receive until the end. If this is the case, it is important to monitor your outflow to ensure that you have enough funding to complete the project.

Monitoring cash flow allows you to have a reference point for your project’s health. For example, if the cash flow coming into your project is lower than your outflow, you will need to adjust your budget. Planning and tracking the cash flow for your project is a key component of budget management.

CAPEX and OPEX

Organizations have a number of different types of expenses, from the wages they pay their employees to the cost of materials for their products. These expenses can be organized into different categories. Two of the most common are CAPEX (capital expenses) and OPEX (operating expenses).

-

CAPEX (capital expenses) are an organization’s major, long-term, upfront expenses, such as buildings, equipment, and vehicles. They are generally for assets that the company will own and keep. The company incurs these expenses because they believe they will create a benefit for the company in the future.

-

OPEX (operating expenses) are the short-term expenses that are required for the day-to-day tasks involved in running the company, such as wages, rent, and utilities. They are often recurring.

You may need to account for both OPEX and CAPEX on your projects. For example, a major software acquisition as part of an IT project could be treated by your organization as a capital expense. The monthly wages paid to a contractor to help deploy the software would be an operating expense. It’s a good idea to talk to your finance or accounting department when you start working on your project budget to see how they determine the difference between OPEX and CAPEX. This will guide you in properly allocating capital and operating expenses for your projects.

Contingency reserves

Sometimes, a project hits a snag and incurs additional expenses. One way to prepare for unplanned costs is by using contingency reserves. Contingency reserves are funds added to the estimated project cost to cover identified risks. These are also referred to as buffers.

To determine the amount of your contingency reserves, you will need to go through the risk management process and identify the risks that are most likely to occur. We will go into more detail on risk management later in the course, but it is important to understand that risks to your project can have an impact on your budget.

Contingency reserves can also be used to cover areas where actual costs turn out to be higher than estimated costs. For example, you may estimate a certain amount for labor costs, but if a contracted worker on your team gets a raise, then the actual costs will be higher than you estimated.

Management reserves

While contingency reserves are used to cover the costs of identified risks, management reserves are used to cover the costs of unidentified risks. For example, if you were managing a construction project and a meteor hit your machinery, you could use management reserves to cover the costs of the damage.

Contingency reserves are an estimated amount, whereas management reserves are generally a percentage of the total cost of the project. To determine a project’s management reserves, you can estimate a percentage of the budget to set aside. This estimate is typically between 5–10%, but the amount is based on the complexity of the project. A project with a more complex scope may require higher management reserves. Note that the project manager will generally need approval from the project sponsor in order to use management reserves.

Phases of risk management

-

Identify the risk. The first phase of the risk management process is to identify and define potential project risks with your team. After all, you can only manage risks if you know what they are.

-

Analyze the risk. After identifying the risks, determine their likelihood and potential impact to your project. Serious risks with a high probability of occurring pose the greatest threat.

-

Evaluate the risk. Next, use the results of your risk analysis to determine which risks to prioritize.

-

Treat the risk. During this phase, make a plan for how to treat and manage each risk. You might choose to ignore minor risks, but serious risks need detailed mitigation plans.

-

Monitor and control the risk. Finally, assign team members to monitor, track, and mitigate risks if the need arises.

Four types of Risk mitigation

Let’s imagine that Office Green uses plant seeds from a company in South America for the majority of its offerings. The plants produced by these seeds are in high demand by Office Green’s customers. However, the local government on the suppliers’ end just announced that it would be imposing a new tax on the exporting of seeds and produce. As a result, the price of the seeds suddenly becomes so high that it is difficult for the company to supply the seeds to Office Green, putting the project at risk of not having these seeds available to purchase.

Avoid

This strategy seeks to sidestep—or avoid—the situation as a whole. In the Office Green example, the team could avoid this risk entirely by considering using another seed that is widely available in several locations.

Minimize

Mitigating a risk involves trying to minimize the catastrophic effects that it could have on the project. The key to minimizing risk starts with realizing that the risk exists. That is why you will usually hear mitigation strategies referred to as workarounds. What if the Office Green team decided to use both the original South American supplier and another supplier from a neighboring country? More than likely, the change in taxation and regulation wouldn’t affect both companies, and this would provide Office Green some flexibility without having to completely eliminate their preferred supplier.

Transfer

The strategy of transferring shifts the responsibility of handling the risk to someone else. The Office Green team could find a supplier in North America that uses the seeds from several other South American countries and purchase the seeds from them instead. This transfers the ownership of South American regulatory risks and costs to that supplier.

Accept

Lastly, you can accept the risk as the normal cost of doing business. Active acceptance of risk usually means setting aside extra funds to pay your way out of trouble. Passive acceptance of risk is the “do nothing” approach. While passive acceptance may be reasonable for smaller risks, it is not recommended for most single point of failure risks. It is also important to be proactive and mitigate risks ahead of time whenever possible, as this may save you from having to accept risks. In the Office Green scenario, the project manager could schedule a meeting with project stakeholders to discuss the increase in South American taxes and how it could impact the project cost. Then, they might decide to actively accept the risk by setting aside additional funds to source the seeds from another supplier, if necessary, or to passively accept the risk of not receiving the seeds at all this season.

Visualizing dependency relationships

In the video, you learned to identify several types of risks. In this reading, we will be discussing the different types of dependencies that can play a critical role in our project’s success.

Types of dependencies

Dependencies are a relationship between two project tasks in which the completion or the initiation of one is reliant on the completion or initiation of the other. Let’s explore four common types of dependencies:

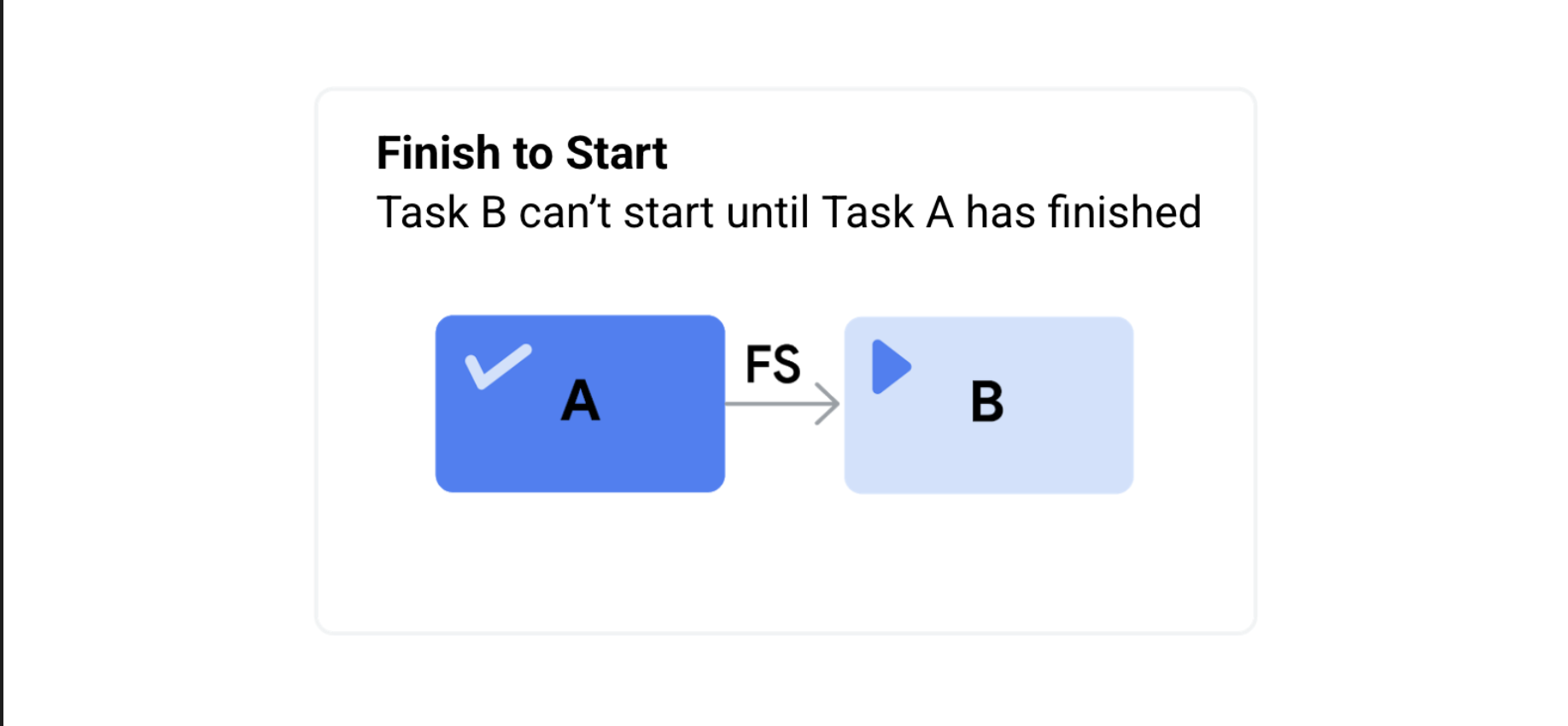

Finish to Start (FS)

In this type of relationship between two tasks, Task A must be completed before Task B can start. This is the most common dependency in project management. It follows the natural progression from one task to another.

Example: Imagine you are getting ready to have some friends over for dinner. You can’t start putting on your shoes (Task B) until you’ve finished putting on your socks (Task A).

Task A: Finish putting on your socks. →Task B: Start putting on your shoes.

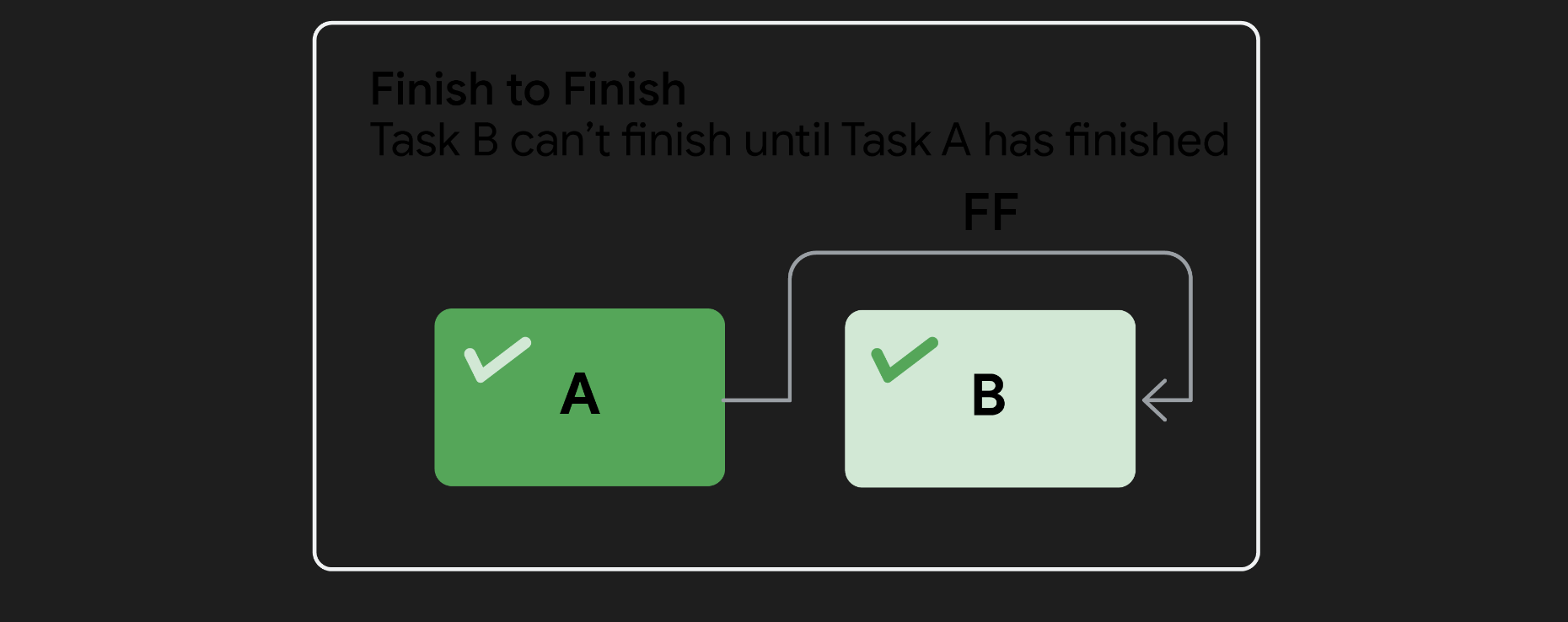

Finish to Finish (FF)

In this model, Task A must finish before Task B can finish. (This type of dependency is not common.)

Example: Earlier in the day, you baked a cake. You can’t finish decorating the cake (Task B) until you finish making the icing (Task A).

Task A: Finish making the icing. →Task B: Finish decorating the cake.

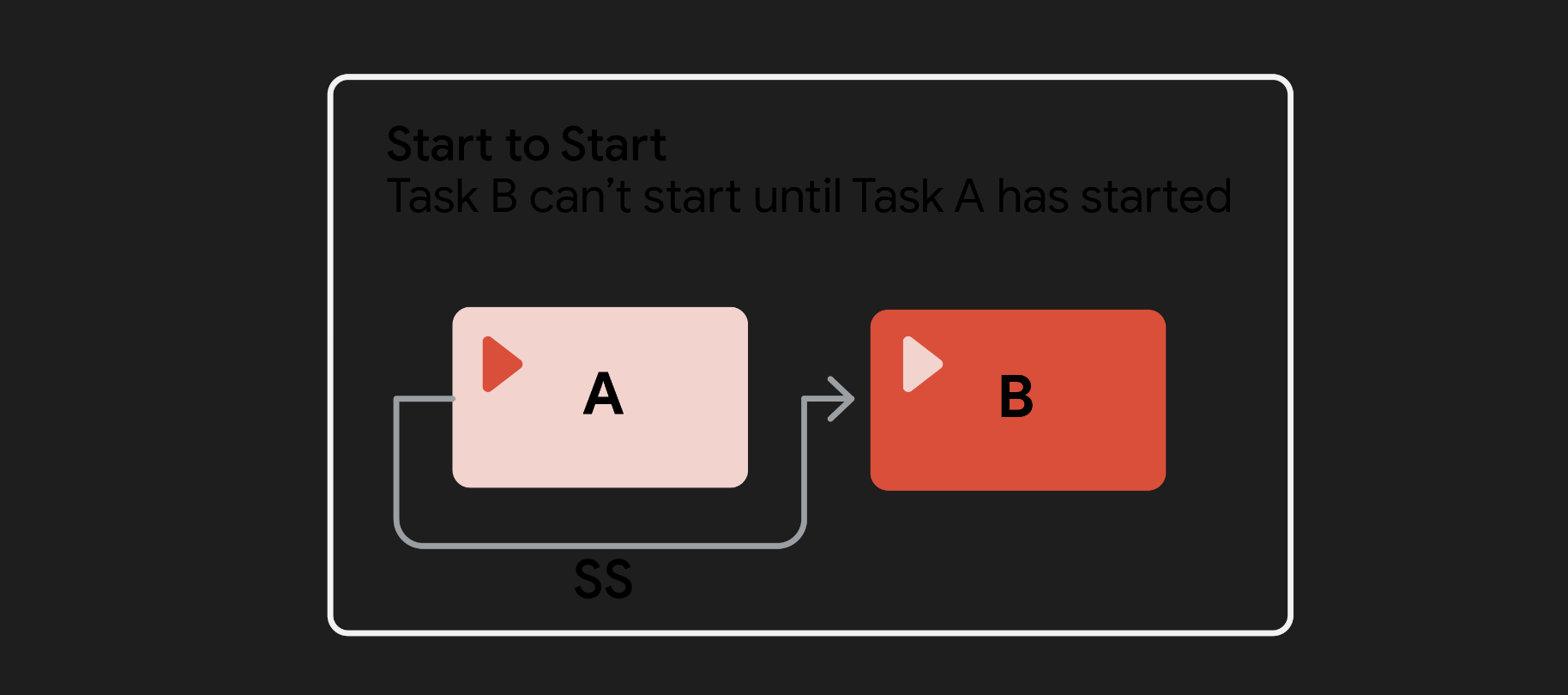

Start to Start (SS)

In this model, Task B can’t begin until Task A begins. This means Tasks A and B start at the same time and run in parallel.

Example: You need to take the train home after work. You can’t get on the train (Task B) until you pay for the train ride (Task A).

Task A: Start by paying for your train ride. →Task B: Start going home by boarding the train.

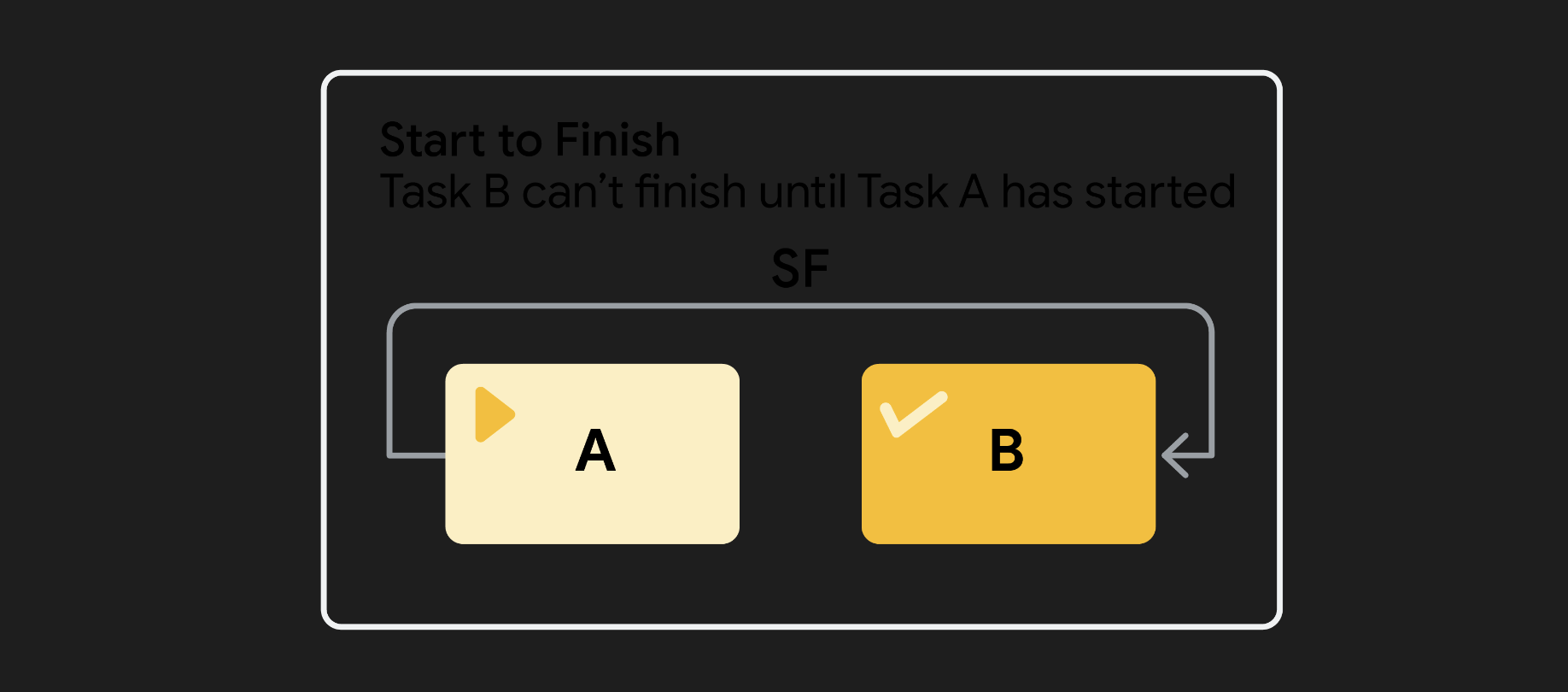

Start to Finish (SF)

In this model, Task A must begin before Task B can be completed.

Example: One of your friends calls to tell you he’ll be late. He can’t finish his shift (Task B) and leave work until his coworker arrives to start her shift (Task A).

Task A: Your friend’s coworker starts her shift. →Task B: Your friend finishes his shift.

Writing an effective escalation email

All projects—even those managed by experienced project managers—occasionally have problems. Your role as the project manager is to help resolve problems and remove barriers that prevent your team from making progress toward your goals. While many problems might be small enough to resolve within your core team, other problems—like a major change in your budget or timeline—may need to be brought to stakeholders for a final decision. Detailing these problems, their potential impact, and the support you need in a clear and direct email to your audience can be an effective communication tool.

Effective escalation emails:

-

Maintain a friendly tone

-

State your connection to the project

-

Explain the problem

-

Explain the consequences

-

Make a request

Let’s discuss these five keys to writing a strong escalation email.

Maintain a friendly tone

When drafting an escalation email, you may feel tempted to get straight to the point, especially when dealing with a stressful and time-sensitive problem. But keep in mind that it is important to address issues with grace. Consider opening your email with a simple show of goodwill, such as “I hope you’re doing well.” When describing the issue, aim for a blameless tone. Above all, keep the email friendly and professional. After all, you are asking for the recipient’s help. Be sure to close your email by thanking the recipient for their time.

State your connection to the project

Introduce yourself early in the email if you have less familiarity with the project stakeholders. Be sure to clearly state your name, role, and relationship to the project. This helps the reader understand why you are reaching out. Keep your introduction brief and to the point—a single sentence should suffice. If you know the person on the receiving end of the escalation email, you can simply reinforce your responsibility on the project before getting straight to the problem.

Explain the problem

Once you greet your recipient and briefly introduce yourself, explain the issue at hand. Clearly state the problem you need to solve. Provide enough context for the reader to understand the issue, but aim to keep your message as concise as possible. Avoid long, dense paragraphs that may obscure your message and tempt the reader to skim.

Explain the consequences

After explaining the problem, clearly outline the consequences. Describe specifically how this issue is negatively impacting the project or how it has the potential to negatively impact the project later in the project timeline. Again, keep your explanation concise and your tone friendly.

Propose a course of action and make a request

This is the central piece of a strong escalation email. In this section, you propose a solution (or solutions) and state what you need from the recipient. A thoughtful solution accompanied by a clear request lets the recipient know how they can help and moves you toward a resolution.

Putting it all together

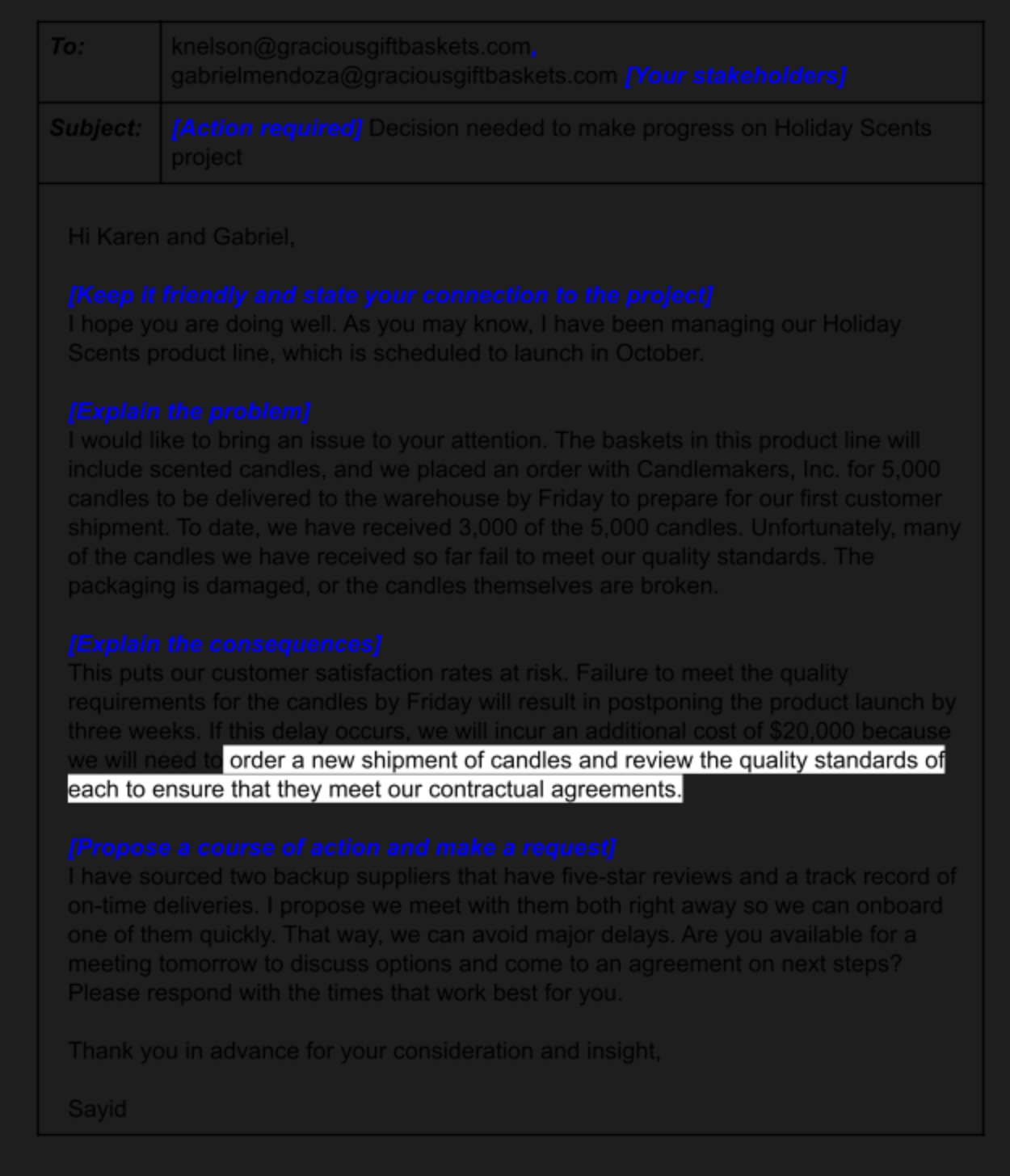

Let’s see how these best practices come together to form a strong escalation email. In the scenario that prompts the email, Sayid, a project manager from a company that sells gift baskets, is having a quality control issue with one of the items in a line of holiday baskets. If the issue is not rectified soon, the product launch will have to be delayed and the company will lose money. In the annotated email example below, Sayid explains the issue to his internal stakeholders and requests a meeting with them.

Alternate text of email:

Alternate text of email:

To: knelson@graciousgiftbaskets.com, gabrielmendoza@graciousgiftbaskets.com [Your stakeholders]

Subject: [Action required] Decision needed to make progress on Holiday Scents project

Hi Karen and Gabriel,

[Keep it friendly and state your connection to the project] I hope you are doing well. As you may know, I have been managing our Holiday Scents product line, which is scheduled to launch in October.

[Explain the problem] I would like to bring an issue to your attention. The baskets in this product line will include scented candles, and we placed an order with Candlemakers, Inc. for 5,000 candles to be delivered to the warehouse by Friday to prepare for our first customer shipment. To date, we have received 3,000 of the 5,000 candles. Unfortunately, many of the candles we have received so far fail to meet our quality standards. The packaging is damaged, or the candles themselves are broken.

[Explain the consequences] This puts our customer satisfaction rates at risk. Failure to meet the quality requirements for the candles by Friday will result in postponing the product launch by three weeks. If this delay occurs, we will incur an additional cost of $20,000 because we will need to order a new shipment of candles and review the quality standards of each to ensure that they meet our contractual agreements.

[Propose a course of action and make a request] I have sourced two backup suppliers that have five-star reviews and a track record of on-time deliveries. I propose we meet with them both right away so we can onboard one of them quickly. That way, we can avoid major delays. Are you available for a meeting tomorrow to discuss options and come to an agreement on next steps? Please respond with the times that work best for you.

Thank you in advance for your consideration and insight,

Sayid

End of email

What Is DMAIC?

DMAIC is a data-driven improvement cycle used to enhance, stabilize, and optimize business processes. It serves as the core tool for driving Six Sigma projects.

The Five Phases of DMAIC

-

Define

- Identify the problem and improvement needs

- Set clear, specific goals

- Document project scope and boundaries

- Establish stakeholder requirements

-

Measure

- Quantify the identified issues

- Gather baseline performance data

- Validate measurement systems

- Determine current process capability

-

Analyze

- Determine root causes

- Identify key process variables

- Validate cause-and-effect relationships

- Prioritize improvement opportunities

-

Improve

- Develop potential solutions

- Test and validate improvements

- Implement change management

- Document new procedures

-

Control

- Monitor implemented changes

- Ensure sustained improvements

- Standardize successful changes

- Document lessons learned

What Is PDCA?

PDCA is a four-stage model (Plan, Do, Check, Act) designed for continuous improvement in business process management, introduced by Dr. Edward Deming in 1950.

The PDCA cycle forms the foundation of Total Quality Management (TQM) and ISO 9001 quality standards and is widely used in areas such as production management, supply chain management, project management, and human resource management. Here is an overview of each stage:

- Plan: This initial phase involves decision-makers analyzing current inefficiencies and identifying the need for change. Key questions include the best methods for implementing change and assessing the associated costs and benefits.

- Do: This stage focuses on executing the planned improvements. Clear communication with affected employees is essential to ensure understanding and support for the changes. If resistance arises, decision-makers should be prepared to address it with appropriate measures.

- Check: In the Check stage, decision-makers assess whether the desired outcomes were achieved by comparing actual results with the expected results.

- Act: Actions in this stage depend on the findings from the Check stage. If the evaluation shows that the improvements were successful, the new processes should be standardized and maintained.

Quality management concepts

-

Quality standards provide requirements, specifications, or guidelines that can be used to ensure that products, processes, or services are fit for achieving the desired outcome. These standards must be met in order for the product, process, or service to be considered successful by the organization and the customer. You will set quality standards with your team and your customer at the beginning of your project. Well-defined standards lead to less rework and schedule delays throughout your project.

-

Quality planning involves the actions of you or your team to establish and conduct a process for identifying and determining exactly which standards of quality are relevant to the project as a whole and how to satisfy them. During this process, you’ll plan the procedures to achieve the quality standards for your project.

-

Quality assurance, or QA, is a review process that evaluates whether the project is moving toward delivering a high-quality service or product. It includes regular audits to confirm that everything is going to plan and that the necessary procedures are being followed. Quality assurance helps you make sure that you and your customers are getting the exact product you contracted for.

-

Quality control, or QC, involves monitoring project results and delivery to determine if they are meeting desired results. It includes the techniques that are used to ensure quality standards are maintained when a problem is identified. Quality control is a subset of quality assurance activities. While QA seeks to prevent defects before they occur, QC aims to identify defects after they have happened and also entails taking corrective action to resolve these issues.

The goals of UAT

Important

UAT is testing that helps a business make sure that a product, service, or process works for its users. The main objectives of UAT are to:

- Demonstrate that the product, service, or process is behaving in expected ways in real-world scenarios.

- Show that the product, service, or process is working as intended.

- Identify issues that need to be addressed before project completion.

Best practices for effective UAT

In order to achieve these goals, UAT needs to be conducted thoughtfully. These best practices can help you administer effective UAT:

-

Define and write down your acceptance criteria. Acceptance criteria are pre-established standards or requirements that a product, service, or process must meet. Write down these requirements for each item that you intend to test. For example, if your project is to create a new employee handbook for your small business, you may set acceptance criteria that the handbook must be a digital PDF that is accessible on mobile devices and desktop.

-

Create the test cases for each item that you are testing. A test case is a sequence of steps and its expected results. It usually consists of a series of actions that the user can perform to find out if the product, service, or process behaved the way it was supposed to. Continuing with the employee handbook example, you could create a test case process in which the user would click to download the PDF of the handbook on their mobile device or desktop to ensure that they could access it without issues.

-

Select your users carefully. It is important to choose users who will actually be the end users of the product, service, or process.

-

Write the UAT scripts based on user stories. These scripts will be delivered to the users during the testing process. A user story is an informal, general explanation of a feature written from the perspective of the end user. In our employee handbook example, a user story might be: As a new employee, I want to be able to use the handbook to easily locate the vacation policy and share it with my team via email.

-

Communicate with users and let them know what to expect. If you can prepare users ahead of time, there will be fewer questions, issues, or delays during the testing process.

-

Prepare the testing environment for UAT. Ensure that the users have proper credentials and access, and try out these credentials ahead of time to ensure they work.

-

Provide a step-by-step plan to help guide users through the testing process. It will be helpful for users to have some clear, easy-to-follow instructions that will help focus their attention on the right places. You can create this plan in a digital document or spreadsheet and share with them ahead of time.

-

Compile notes in a single document and record any issues that are discovered. You can create a digital spreadsheet or document that corresponds to your plan. It can have designated areas to track issues for each item that is tested, including the users’ opinions on the severity of each issue. This will help you prioritize fixes.

Managing UAT feedback

Users provide feedback after performing UAT. This feedback might include positive comments, bug reports, and change requests. As the project manager, you can address the different types of feedback as follows:

-

Bugs or issues: Users might report technical issues, also known as bugs, or other types of issues after performing UAT. You can track and monitor these issues in a spreadsheet or equivalent system and prioritize which issues to fix. For instance, critical issues, such as not being able to access, download, or search the employee handbook, need to be prioritized over non-critical issues, such as feedback on the cover art of the handbook.

-

Change requests: Sometimes the user might suggest minor changes to the product, service, or process after UAT. These types of requests or changes should also be managed and prioritized. Depending on the type and volume of the requests, you may want to share this data with your primary stakeholders, and you may also need to adjust your project timeline to implement these new requests.

Managing UAT Feedback

Types of Feedback

Users provide different types of feedback after performing UAT, including:

- Positive comments

- Bug reports

- Change requests

Addressing Different Types of Feedback

Bugs and Issues

Critical vs Non-Critical

Users might report technical issues (bugs) or other types of issues after UAT. Track and prioritize these issues based on severity:

- Critical issues (high priority): Problems that prevent core functionality (e.g., inability to access or download)

- Non-critical issues (lower priority): Cosmetic or minor concerns (e.g., feedback on visual elements)

Tracking Process:

- Create a dedicated spreadsheet or tracking system

- Document all reported issues

- Assess severity of each issue

- Prioritize fixes based on impact

- Monitor resolution progress

Change Requests

Managing Changes

Users may suggest modifications to the product, service, or process after UAT. Handle these requests by:

- Documenting all requested changes

- Evaluating impact and feasibility

- Prioritizing based on value and effort

- Communicating with stakeholders

- Adjusting project timeline if needed

Best Practices for UAT Feedback Management

Key Recommendations

- Maintain clear communication channels with users

- Document all feedback systematically

- Establish a clear process for evaluating and prioritizing issues

- Keep stakeholders informed of significant changes

- Plan for timeline adjustments when implementing major changes

- Create a feedback loop to verify fixes

Quality Management Concepts

Core Quality Components

Key Elements

Quality management consists of several essential components:

- Quality Standards

- Quality Planning

- Quality Assurance (QA)

- Quality Control (QC)

Quality Standards

Standards provide requirements, specifications, or guidelines ensuring that products, processes, or services are fit for achieving desired outcomes. These must be met for project success and should be:

- Clearly defined at project start

- Agreed upon by team and stakeholders

- Measurable and verifiable

- Aligned with organizational goals

Quality Planning

Planning Process

Quality planning involves:

- Identifying relevant quality standards

- Determining how to satisfy these standards

- Creating procedures for quality achievement

- Documenting the quality management approach

Quality Assurance (QA)

QA is an ongoing evaluation process that:

- Reviews project progress toward quality goals

- Includes regular audits

- Ensures procedures are being followed

- Focuses on preventing defects before they occur

- Validates alignment with customer requirements

Quality Control (QC)

QC vs QA

While QA prevents defects, QC focuses on identifying defects after they occur. Quality Control:

- Monitors specific project results

- Determines if they meet quality standards

- Identifies defects after they happen

- Recommends corrective actions

- Validates fixes and improvements

Process Improvement Methodologies

DMAIC Methodology

Definition

DMAIC is a data-driven improvement cycle used to enhance, stabilize, and optimize business processes. It serves as the core tool for driving Six Sigma projects.

The Five Phases of DMAIC

-

Define

- Identify the problem and improvement needs

- Set clear, specific goals

- Document project scope and boundaries

- Establish stakeholder requirements

-

Measure

- Quantify the identified issues

- Gather baseline performance data

- Validate measurement systems

- Determine current process capability

-

Analyze

- Determine root causes

- Identify key process variables

- Validate cause-and-effect relationships

- Prioritize improvement opportunities

-

Improve

- Develop potential solutions

- Test and validate improvements

- Implement change management

- Document new procedures

-

Control

- Monitor implemented changes

- Ensure sustained improvements

- Standardize successful changes

- Document lessons learned

PDCA Cycle

Overview

The Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle is a fundamental model for continuous improvement, forming the foundation of Total Quality Management (TQM) and ISO 9001 standards.

Four Stages of PDCA

- Plan

Planning Phase

- Analyze current inefficiencies

- Identify needs for change

- Assess implementation methods

- Evaluate costs and benefits

- Set clear objectives

- Do

Implementation Phase

- Execute planned improvements

- Communicate changes clearly

- Manage resistance

- Document progress

- Collect data

- Check

Evaluation Phase

- Compare results to expectations

- Measure effectiveness

- Identify any gaps

- Document findings

- Gather feedback

- Act

Action Phase

- Standardize successful changes

- Address any shortcomings

- Plan next improvements

- Share lessons learned

- Update documentation

Quality Management Implementation

Best Practices for Quality Management

Key Success Factors

- Leadership commitment

- Employee involvement

- Process approach

- Continuous improvement

- Evidence-based decision making

- Customer focus

Quality Tools and Techniques

Documentation

- Quality Management Plan

- Process Documentation

- Standard Operating Procedures

- Quality Metrics Dashboard

- Audit Reports

Measurement Tools

- Control Charts

- Pareto Analysis

- Cause-and-Effect Diagrams

- Check Sheets

- Histograms

Quality Review Process

Review Components

- Regular quality audits

- Performance metrics tracking

- Customer feedback analysis

- Process compliance checks

- Improvement opportunity identification

Continuous Improvement Cycle

Ongoing Process

The continuous improvement cycle involves:

- Regular assessment of processes

- Identification of improvement opportunities

- Implementation of changes

- Measurement of results

- Standardization of successful changes

Quality Management Integration

Alignment with Project Management

Integration Points

Quality management should be integrated with:

- Project planning

- Risk management

- Change control

- Stakeholder communication

- Resource allocation

Stakeholder Involvement

Engagement Strategies

- Regular quality status updates

- Involvement in quality reviews

- Feedback collection and analysis

- Clear communication of quality metrics

- Collaborative problem-solving

Documentation and Reporting

Key Documents

Maintain comprehensive documentation of:

- Quality standards and requirements

- Process documentation

- Quality metrics and KPIs

- Audit findings and actions

- Improvement initiatives

- Lessons learned

The Agile Manifesto

The Agile values refer to the following four statements:

-

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

-

Working software over comprehensive documentation

-

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

-

Responding to change over following a plan

Agile experts see these values as important underpinnings of the highest performing teams, and every team member should strive to live by these values to apply the full benefits of Agile.

The same is true for the 12 principles, which are at the core of every Agile project:

-

“Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.” Whether you are working to create a product for your company or for a customer, chances are that someone is awaiting its delivery. If that delivery is delayed, the result is that the customer, user, or organization is left waiting for that added value to their lives and workflows. Agile emphasizes that delivering value to users early and often creates a steady value stream, increasing you and your customer’s success. This will build trust and confidence through continuous feedback as well as early business value realization.

-

“Welcome changing requirements, even late in development.” When working in Agile, it’s important to be agile. That means being able to move swiftly, shifting direction whenever necessary. That also means that you and your team are constantly scanning your environment to make sure necessary changes are factored into the plans. Acknowledging and embracing that your plans may change (once, twice, or several times) ensures that you and your customers are maximizing your success.

-

“Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter timescale.” Delivering your product in small, frequent increments is important because it allows time and regular opportunities for stakeholders—including customers—to give feedback on its progress. This ensures that the team never spends too much time going down the wrong path.

-